1. Introduction: From Concept to Construct

In Part 1, electrogenomic Formulations was introduced as a conceptual rupture in how medicines are imagined, not as static doses, but as systems capable of sensing, interpreting, and responding to molecular disease signals in real time. That discussion deliberately focused on why such a paradigm is emerging. Part 2 answers the harder and more consequential question: how does this actually get built?

This section moves electrogenomics out of theory and into matter. It examines the physical substrates. polymers, hydrogels, nanoparticles, and hybrid bioelectronic scaffolds, that make it possible for an electrogenomic formulations to “listen” to gene expression and act upon it. These are not speculative materials; many are already implanted in patients, embedded in approved devices, or used in advanced drug delivery systems. What changes in electrogenomic formulations is not the material itself, but the logic embedded within it.

Crucially, Part 2 is written from the perspective of the formulation scientist rather than the algorithm designer. Electrogenomic formulations systems do not assemble themselves. They are selected, tuned, stabilized, coated, tested, scaled, and defended under regulatory scrutiny. Every decision, from aptamer sequence design to polymer conductivity, from mRNA threshold definition to release kinetics, mirrors the same trade-offs formulators already navigate, only now under genomic rather than pharmacokinetic control.

This section, therefore, serves two purposes. First, it provides a deep technical map of the material platforms that enable electrogenomic formulations behavior. Second, and more importantly, it presents a step-by-step construction logic, a practical workflow showing how a real pharmaceutical scientist would design, characterize, and manufacture an electrogenomic formulations system within the constraints of stability, quality, and regulation.

The latter sections ground this framework in biological reality and clinical need. Electrogenomics is explored not as a universal solution, but as a targeted response to diseases defined by episodic, localized, or transcript-driven pathology, epilepsy, autoimmune flares, cancer, neurodegeneration, wound repair, and gene therapy. Finally, the article situates electrogenomic formulations within today’s pharmaceutical landscape, highlighting where proto-electrogenomic thinking is already in use, often unnoticed, across biosensing, smart implants, and transcript-guided dosing.

If Part 1 asked whether Electrogenomic Formulations medicines can think, Part 2 demonstrates how they are engineered to do so, quietly, materially, and within the hands of formulation science.

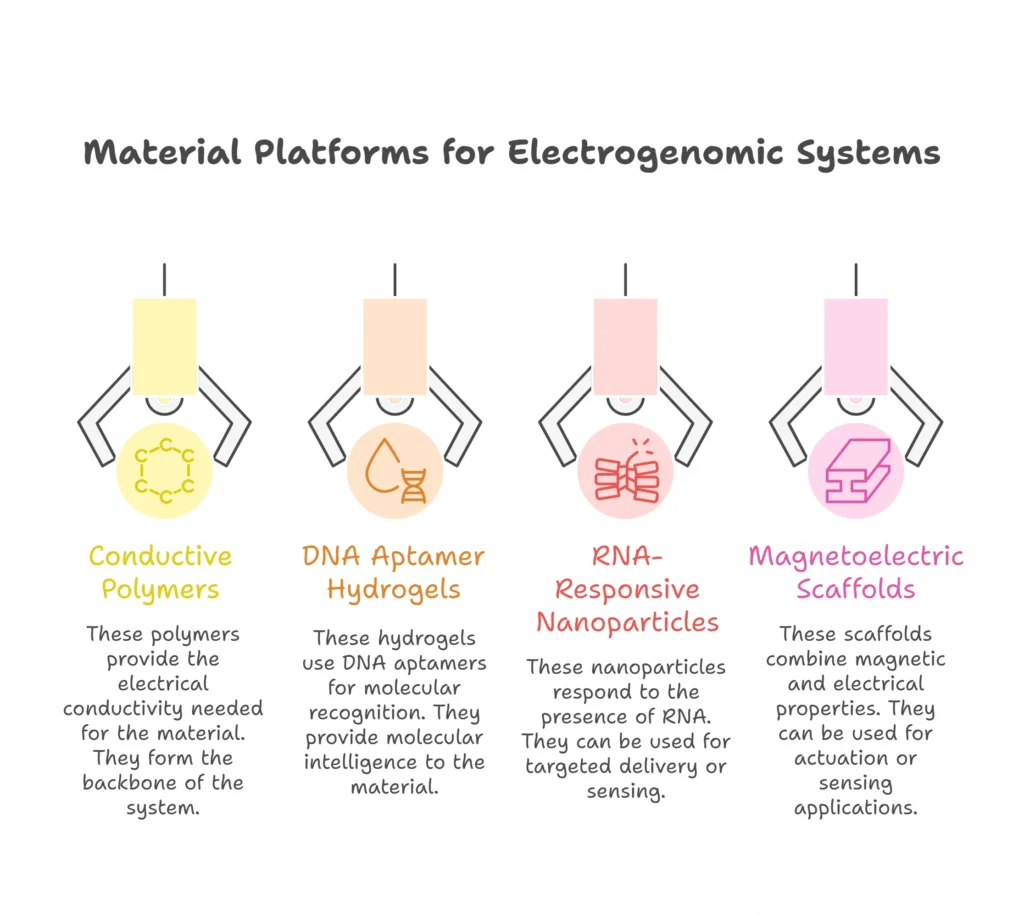

2. Material Platforms That Make Electrogenomic Formulations System Possible

Electrogenomic Formulations systems do not emerge from software or algorithms alone. They are physical, chemical, and biological constructs. engineered matter capable of sensing gene expression, transducing molecular events into electrical or physicochemical signals, and responding with precision drug or gene release. This section dives into the actual material platforms enabling this convergence.

2.1 Conductive Polymers: The Electrical Backbone

Conductive polymers form the nervous system of electrogenomic formulations platforms. Unlike metals, they are soft, biocompatible, and capable of interfacing directly with biological tissues.

Key materials include polypyrrole (PPy), PEDOT: PSS, polyaniline, and doped thiophene derivatives. These polymers can be engineered to change oxidation state, conductivity, or swelling behavior in response to biochemical signals.

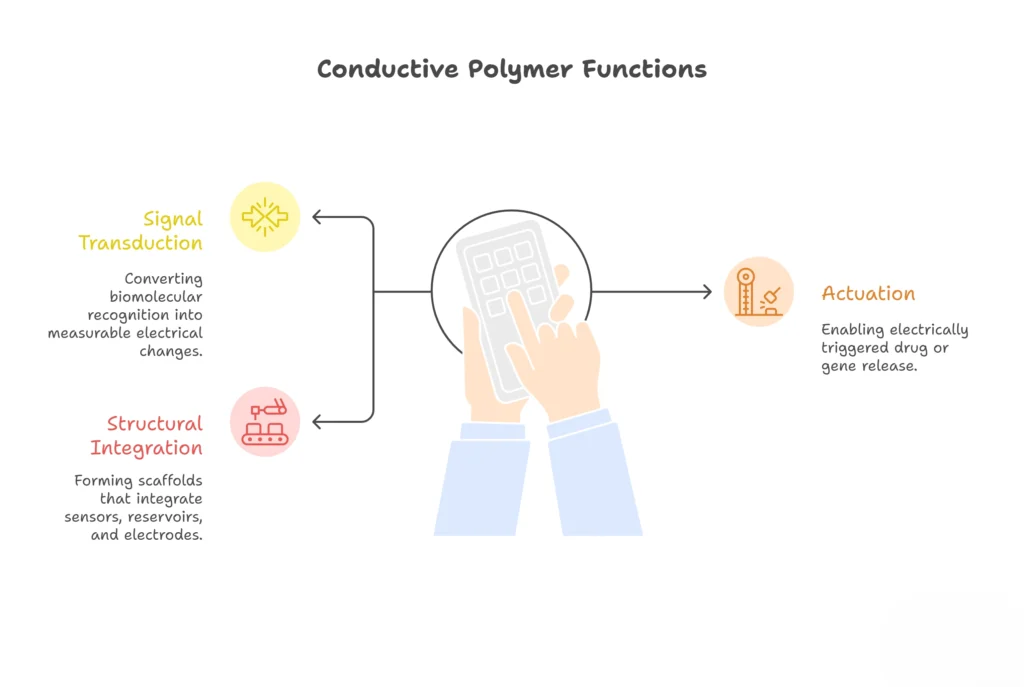

This article explores the multifaceted roles of conductive polymers within electrogenomic formulations constructs. These roles encompass signal transduction, where biomolecular recognition events are translated into electrical signals; actuation, facilitating electrically controlled drug or gene release; and structural integration, providing a framework for integrating sensors, reservoirs, and electrodes.

In electrogenomic Formulations constructs, conductive polymers serve three core functions:

2.11 Signal Transduction

Conductive polymers (CPs) are uniquely suited for signal transduction in electrogenomic formulations constructs due to their ability to convert biomolecular recognition events into measurable electrical signals. This capability stems from their electronic properties, which are highly sensitive to changes in their chemical environment. When a target biomolecule interacts with a recognition element (e.g., an aptamer, antibody, or enzyme) immobilized on the CP surface, it induces a change in the CP’s conductivity, redox potential, or other electrical characteristics. This change can then be detected using electrochemical techniques, providing a quantitative measure of the target biomolecule’s concentration.

Several mechanisms contribute to the signal transduction process:

- Charge Transfer: The binding of a charged biomolecule to the CP can directly alter the polymer’s charge carrier density, leading to a change in conductivity.

- Redox Reactions: Enzyme-catalyzed reactions can generate redox-active species that interact with the CP, causing a change in its redox state and electrical properties.

- Conformational Changes: Biomolecular binding can induce conformational changes in the CP, affecting its electronic structure and conductivity.

- Doping/Dedoping: The binding event can promote the insertion or expulsion of ions (dopants) into or out of the CP matrix, modulating its conductivity.

The choice of CP and recognition element is crucial for optimizing the sensitivity and selectivity of the electrogenomic sensor. Polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) are commonly used CPs due to their biocompatibility, ease of synthesis, and tunable electronic properties. Aptamers, short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind to specific targets with high affinity, are frequently employed as recognition elements due to their versatility and ease of modification.

Examples:

- An aptamer-based sensor for detecting thrombin, a coagulation protein, utilizes a PPy film modified with a thrombin-binding aptamer. Upon thrombin binding, the aptamer undergoes a conformational change, altering the PPy’s conductivity and generating a measurable signal.

- A glucose biosensor employs a PEDOT film modified with glucose oxidase (GOx). GOx catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, producing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which oxidizes the PEDOT film, resulting in a change in its electrochemical properties.

2.12 Actuation:

Conductive polymers can also function as actuators in electrogenomic formulations constructs, enabling electrically triggered drug or gene release. This capability arises from their ability to undergo reversible volume changes in response to electrical stimulation. When a CP is oxidized or reduced, ions and solvent molecules move into or out of the polymer matrix, causing it to swell or shrink. This volume change can be harnessed to control the release of therapeutic agents encapsulated within the CP or attached to its surface.

Several electrogenomic formulations strategies are employed for electrically triggered release:

- Electrically Controlled Swelling/Shrinking: A drug-loaded CP film is subjected to an electrical potential. The resulting swelling or shrinking of the polymer matrix releases the encapsulated drug.

- Electrochemical Degradation: The CP is designed to degrade upon electrochemical oxidation or reduction, releasing the therapeutic agent.

- Electrically Triggered Cleavage: A therapeutic agent is linked to the CP via an electrochemically cleavable linker. Applying an electrical potential breaks the linker, releasing the agent.

- Electroporation: The CP is used to create transient pores in cell membranes, allowing for the delivery of genes or drugs into the cells.

The release kinetics can be controlled by adjusting the applied voltage, pulse duration, and frequency of electrogenomic formulations. Furthermore, the release can be spatially controlled by applying the electrical stimulus to specific regions of the CP film.

Examples:

- A PEDOT film loaded with dexamethasone, an anti-inflammatory drug, can be used to treat inflammation. Applying an electrical potential to the film causes it to release dexamethasone, reducing inflammation.

- A PANI film modified with DNA can be used for gene delivery. Applying an electrical potential to the film causes it to release the DNA, which can then be taken up by cells.

2.13 Structural Integration:

Conductive polymers serve as versatile scaffolds for integrating various components of electrogenomic formulations constructs, including sensors, reservoirs, and electrodes. Their ability to be easily synthesized, patterned, and functionalized makes them ideal for creating complex micro- and nano-devices.

CPs can be used to:

- Support and Encapsulate Sensors: CPs can be used to create a matrix that supports and protects sensitive biosensors, enhancing their stability and longevity.

- Form Reservoirs for Therapeutic Agents: CPs can be used to create micro- or nano-reservoirs for storing and releasing drugs or genes.

- Integrate Electrodes: CPs can be directly deposited onto electrodes, improving their biocompatibility and enhancing their electrochemical performance.

- Create Microfluidic Channels: CPs can be patterned to create microfluidic channels for delivering reagents and removing waste products.

The integration of these components into a single platform enables the creation of sophisticated electrogenomic formulations devices that can perform multiple functions, such as sensing, actuation, and drug delivery, in a coordinated manner.

Examples:

- A microfluidic device for cell culture incorporates a PEDOT electrode for stimulating cells, a PPy sensor for monitoring cell metabolism, and a drug-loaded CP reservoir for delivering therapeutic agents.

- An implantable biosensor for continuous glucose monitoring integrates a glucose oxidase-modified PEDOT electrode, a microreservoir containing insulin, and a feedback control system that regulates insulin release based on the glucose level.

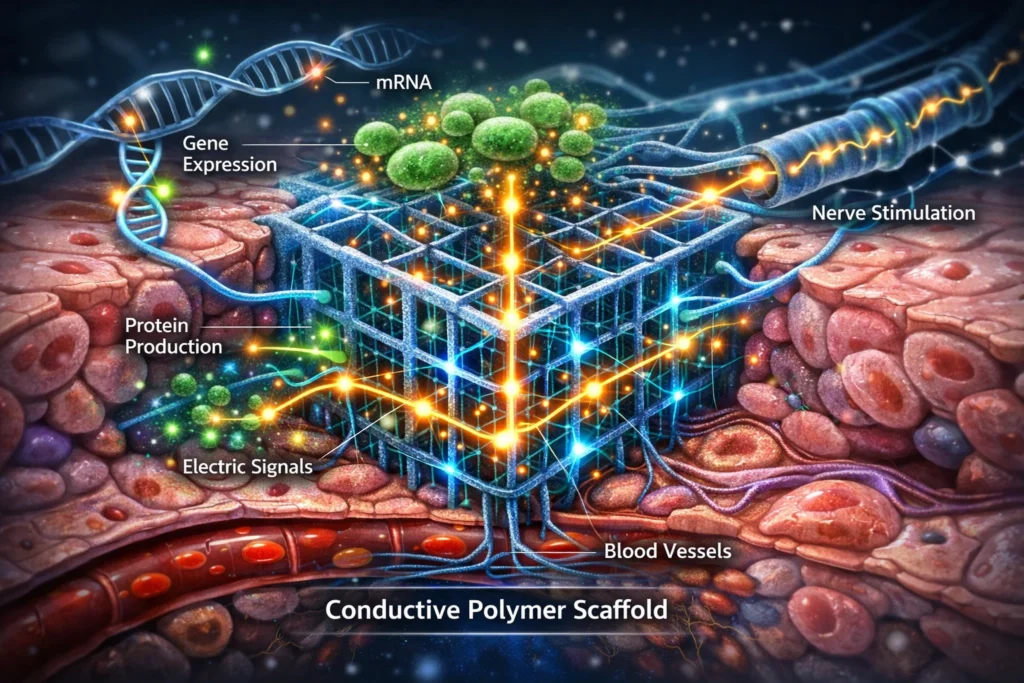

Real World Example: PEDOT:PSS-Coated Neural Electrodes: From Deep Brain Stimulation to Inflammatory Sensing and Drug Delivery

Electrogenomic Formulations System: Cross-sectional illustration of a conductive polymer scaffold embedded in tissue, showing electrical signal flow triggered by gene expression changes.

PEDOT:PSS (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate) has emerged as a prominent material in neural electrode technology, particularly in the context of deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Parkinson’s disease. DBS involves implanting electrodes deep within the brain to deliver electrical impulses that modulate neural activity and alleviate motor symptoms associated with the disease.

The success of PEDOT:PSS in DBS stems from its unique properties:

- Enhanced Charge Injection: PEDOT:PSS is an organic conductive polymer that significantly improves the charge injection capacity of electrodes. This is crucial for efficient and reliable stimulation of neural tissue. By coating electrode surfaces with PEDOT:PSS, the impedance is reduced, allowing for lower stimulation voltages and reduced power consumption.

- Biocompatibility: PEDOT:PSS exhibits good biocompatibility, minimizing adverse reactions from the surrounding brain tissue. This is essential for long-term implantation and functionality of the electrodes. While not perfectly inert, the material’s biocompatibility profile is generally favorable compared to bare metal electrodes.

- Mechanical Flexibility: PEDOT:PSS coatings can be applied as thin films, preserving the mechanical flexibility of the underlying electrode substrate. This is important for minimizing tissue damage during implantation and ensuring conformability to the complex brain anatomy.

- Reduced Artifacts: The improved charge injection and lower impedance associated with PEDOT:PSS coatings can reduce stimulation artifacts, leading to more precise and reliable neural modulation.

The clinical adoption of PEDOT:PSS-coated electrodes in DBS for Parkinson’s disease demonstrates their safety and efficacy in a real-world setting. The technology has been refined over years of research and clinical trials, establishing a solid foundation for further advancements in electrogenomic Formulations.

Emerging Applications: Inflammatory Sensing

Beyond DBS, researchers are now exploring the potential of PEDOT:PSS-coated electrodes for sensing inflammatory processes within the brain. Inflammation plays a critical role in various neurological disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases, stroke, and traumatic brain injury. The ability to monitor inflammatory markers in real-time could provide valuable insights into disease progression and treatment efficacy.

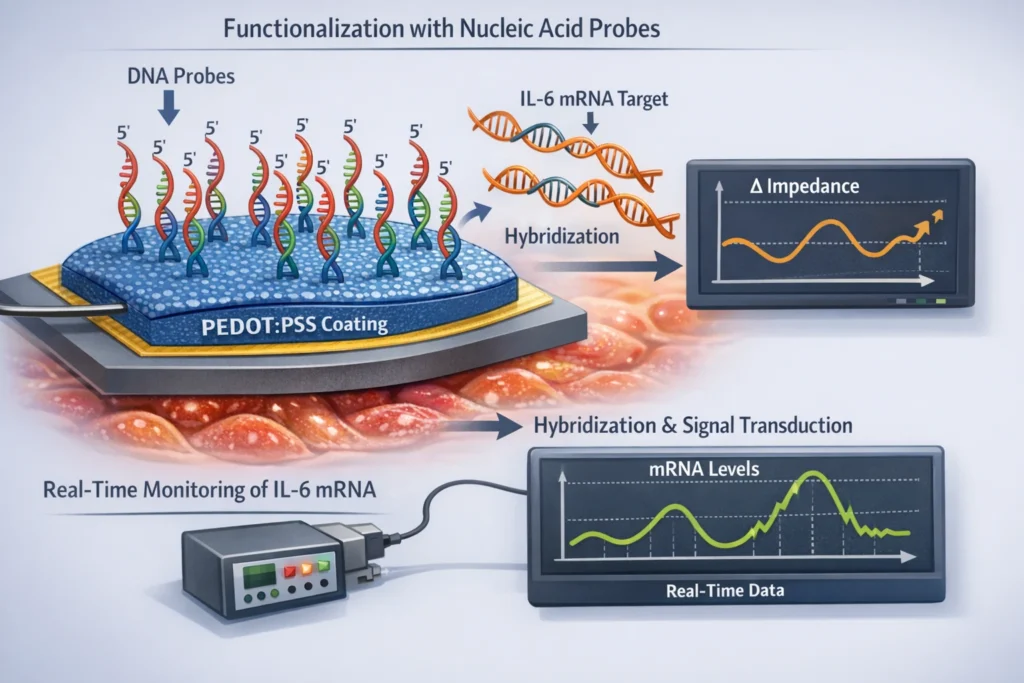

One promising approach involves modifying PEDOT:PSS coatings to detect specific inflammatory gene upregulation, such as IL-6 mRNA (interleukin-6 messenger RNA). IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is often elevated in response to neural injury or disease.

The sensing mechanism typically involves:

- Functionalization with Nucleic Acid Probes: The PEDOT:PSS coating is functionalized with nucleic acid probes that are complementary to the target mRNA sequence (e.g., IL-6 mRNA).

- Hybridization and Signal Transduction: When the target mRNA is present, it hybridizes with the probe, leading to a change in the electrical properties of the PEDOT:PSS coating. This change can be detected as a shift in impedance, capacitance, or other electrochemical parameters.

- Real-Time Monitoring: The electrode can continuously monitor the levels of the target mRNA, providing real-time information about the inflammatory state of the surrounding tissue.

This approach offers several advantages:

- High Sensitivity: Electrochemical detection methods can be highly sensitive, allowing for the detection of low levels of inflammatory markers through electrogenomic formulations.

- Spatial Resolution: The use of microelectrodes allows for localized sensing of inflammation within specific brain regions.

- Continuous Monitoring: The ability to continuously monitor inflammatory markers provides a dynamic picture of the inflammatory response, which can be crucial for understanding disease progression and treatment effects.

Emerging Applications: Local Drug Delivery

In addition to sensing, PEDOT:PSS-coated electrodes can also be used for local drug delivery. This approach offers the potential to deliver therapeutic agents directly to the site of inflammation or neural injury, minimizing systemic side effects and maximizing therapeutic efficacy through electrogenomic formulations construct.

The drug delivery mechanism typically involves:

- Drug Encapsulation: The therapeutic agent is encapsulated within a biocompatible matrix, such as a hydrogel or liposome, that is incorporated into the PEDOT:PSS coating which is highly utilize in electrogenomic formulations.

- Electrically Controlled Release: The release of the drug is controlled by applying an electrical stimulus to the PEDOT:PSS coating. This stimulus can trigger the degradation of the matrix, the release of the drug from the electrogenomic formulations matrix, or the electro-osmotic transport of the drug through the coating.

- Localized Delivery: The drug is released directly into the surrounding tissue, minimizing systemic exposure and maximizing the concentration at the target site.

Integration of Sensing and Drug Delivery

The combination of inflammatory sensing and local drug delivery represents a powerful approach for closed-loop neuromodulation. In this scenario, the PEDOT:PSS-coated electrode acts as both a sensor and an actuator, continuously monitoring the inflammatory state of the brain and delivering therapeutic agents as needed.

For example, the electrode could monitor IL-6 mRNA levels and, when levels exceed a certain threshold, trigger the release of an anti-inflammatory drug. This closed-loop system could provide personalized and adaptive therapy, optimizing treatment efficacy and minimizing side effects.

2.2 DNA Aptamer Hydrogels: Molecular Intelligence

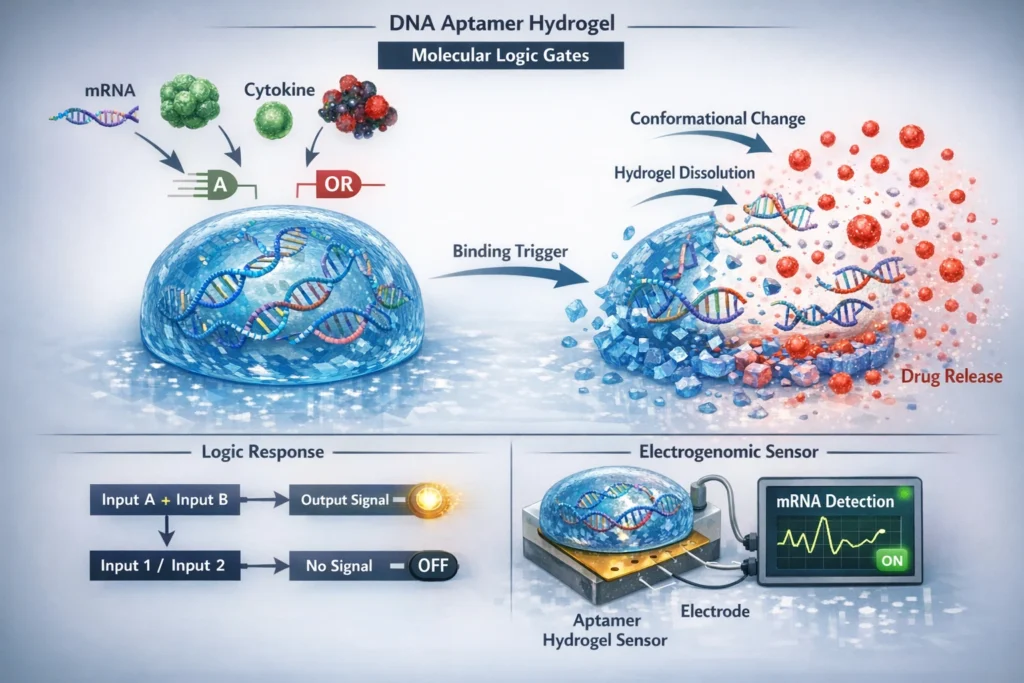

The fascinating realm of DNA aptamer hydrogels, highlighting their ability to function as molecular logic gates. These hydrogels, composed of short oligonucleotide sequences known as aptamers, exhibit remarkable target specificity, binding to molecules such as mRNA fragments, transcription factors, cytokines, and oncogenic proteins. When integrated into hydrogels, these aptamers imbue the material with responsiveness, enabling it to undergo conformational changes, trigger crosslink cleavage, and release encapsulated therapeutics upon target binding. This will delve into the functionality and potential applications of aptamer hydrogels, with a particular focus on their electrogenomic formulations relevance as transcriptomic sensors.

DNA aptamers are short, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that can bind to specific target molecules with high affinity and specificity. These target molecules can range from small molecules like drugs and metabolites to large biomolecules like proteins and even whole cells. Aptamers are typically generated through an iterative process called Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX). This process involves repeated rounds of selection, amplification, and partitioning to isolate aptamers that bind to the target molecule with the desired affinity and specificity.

The unique binding properties of aptamers make them attractive building blocks for creating responsive hydrogels. Hydrogels are three-dimensional networks of crosslinked polymers that can absorb and retain large amounts of water. By incorporating aptamers into the hydrogel network, it is possible to create materials that respond to the presence of specific target molecules.

Functionality of Aptamer Hydrogels

Aptamer hydrogels as advance electrogenomic formulations can be designed to exhibit a variety of responses upon target binding, including:

- Collapse or Swelling: The binding of the target molecule to the aptamer can induce a conformational change in the aptamer, which in turn can alter the crosslinking density of the hydrogel. This can lead to a change in the swelling or collapse of the hydrogel. For example, an aptamer that binds to a target molecule and causes the hydrogel to collapse could be used to create a sensor for that molecule. Conversely, an aptamer that causes the hydrogel to swell upon target binding could be used to release a electrogenomic formulations drug or other therapeutic agent.

- Trigger Cleavage of Crosslinks: Aptamers can be designed to trigger the cleavage of crosslinks within the hydrogel network upon target binding. This can be achieved by incorporating cleavable linkers into the hydrogel network that are sensitive to specific enzymes or chemical conditions. When the target molecule binds to the aptamer, it can activate an enzyme or create a chemical environment that cleaves the crosslinks, leading to the degradation of the hydrogel.

- Release of Encapsulated Therapeutics: Aptamer hydrogels can be used to encapsulate and release therapeutic agents in a controlled manner. The electrogenomic formulations, therapeutic agent can be physically entrapped within the hydrogel network or chemically conjugated to the hydrogel matrix. Upon target binding, the hydrogel can undergo a conformational change or degrade, leading to the release of the therapeutic agent. This approach can be used to deliver drugs, proteins, or other therapeutic agents to specific locations in the body or to release them in response to specific disease conditions.

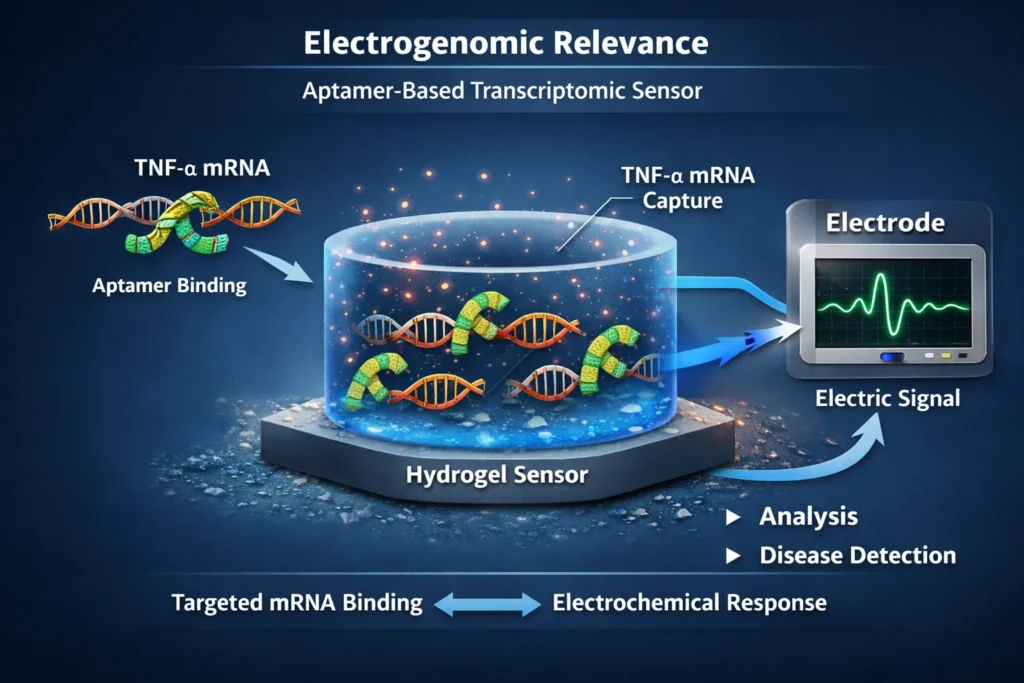

Electrogenomic Formulations Relevance: Transcriptomic Sensors

The ability of aptamer hydrogels to respond to specific target molecules makes them particularly attractive for use as transcriptomic sensors. By designing aptamers that bind to disease-specific transcripts, such as TNF-α mRNA, the hydrogel can be used to detect the presence of these transcripts in biological samples. This can be useful for diagnosing diseases, monitoring disease progression, and evaluating the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

The electrogenomic formulations relevance of aptamer hydrogels stems from their potential to be integrated with electronic devices. For example, an aptamer hydrogel could be used to coat a microelectrode. When the target transcript binds to the aptamer, it could induce a change in the electrical properties of the hydrogel, which could be detected by the microelectrode. This would allow for the real-time monitoring of transcript levels in biological samples.

Case Study: Tumor-Specific MicroRNA-Responsive Hydrogel

Researchers at MIT demonstrated a DNA hydrogel that dissolves only in the presence of a specific microRNA signature associated with tumor cells. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules that play a crucial role in regulating gene expression. Certain miRNAs are known to be upregulated in specific types of cancer cells, making them attractive targets for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

The researchers designed a DNA hydrogel that was crosslinked by DNA strands that were complementary to a specific microRNA that is overexpressed in tumor cells. In the absence of the target microRNA, the hydrogel remained intact. However, when the target microRNA was present, it hybridized to the complementary DNA strands, disrupting the crosslinks and causing the hydrogel to dissolve.

The researchers encapsulated doxorubicin, a common chemotherapy drug, within the hydrogel. When the hydrogel was exposed to tumor cells, the microRNA signature of the tumor cells triggered the dissolution of the hydrogel, releasing the doxorubicin selectively inside the tumor microenvironment. This targeted drug delivery approach has the potential to reduce the side effects of chemotherapy and improve the efficacy of cancer treatment.

Conclusion: When Materials Begin to Decide

Electrogenomic formulations do not begin with genes, and they do not end with devices. They begin with materials, quiet, engineered matter designed to sense, interpret, and respond. In Part 2, these materials were not treated as passive carriers, but as active participants in therapeutic logic. Conductive polymers become electrical interpreters. DNA aptamer hydrogels become molecular listeners. RNA-responsive nanoparticles become intracellular gatekeepers. Magnetoelectric scaffolds become silent communicators between the external world and internal biology.

Individually, none of these platforms are revolutionary. Each already exists within modern pharmaceutical or biomedical research. What transforms them into electrogenomic formulations is how they are assembled, not to deliver a fixed dose, but to execute a conditional response. In this context, formulation is no longer about solubility alone, nor release alone, nor stability alone. It becomes about decision-making under biological uncertainty.

Electrogenomic materials do not ask whether a drug should be released at a predetermined time. They ask whether a pathological signal is present, whether its magnitude justifies intervention, and whether the response should be amplified, delayed, or withheld. This shift, from time-based pharmaceutics to signal-based pharmaceutics, is subtle in language but profound in consequence.

What emerges from this material convergence is not a futuristic medicine, but a more disciplined one. Electrogenomic formulations do not overpower biology; they negotiate with it. They wait for transcripts to rise, for inflammatory cascades to declare themselves, for oncogenic signals to cross thresholds. Only then do they act, locally, transiently, and reversibly.

For the formulation scientist, this represents neither a departure from classical training nor its replacement. It is an extension. The same instincts that govern excipient compatibility, diffusion control, coating integrity, and stability now govern electrical fidelity, molecular selectivity, and transcript responsiveness. The tools evolve, but the responsibility remains the same: to translate complexity into control.

Part 2 has shown that electrogenomic formulations are not built from imagination, but from materials already in our hands, rearranged with a new intent. What remains unanswered is not whether such systems are possible, but whether formulators are prepared to assemble them deliberately.

That question is no longer theoretical. And it is precisely where Part 3 of electrogenomic formulations begins. Stay tuned!

References

- Nezakati, T., Seifalian, A. M., Tan, A. & Seifalian, A. Conductive Polymers: Opportunities and Challenges in Biomedical Applications. Chem. Rev. 118(14), 6766–6843. (Review on conductive polymers for biomedical use, including PEDOT, PANI, polypyrrole).

- Le, T.-H., Kim, Y. & Yoon, H. Electrical and Electrochemical Properties of Conducting Polymers. Polymers 9(4), 150 (2017). (Characteristics and fabrication of conductive polymers relevant to biosensing and stimulation).

- Svirskis, D., Travas-Sejdic, J., Rodgers, A. & Garg, S. Electrochemically controlled drug delivery based on intrinsically conducting polymers. J. Controlled Release (2010). (Foundational example of drug release using conducting polymers in controlled delivery).

- Hosseini-Nassab, N., Samanta, D., Abdolazimi, Y., Annes, J. P. & Zare, R. N. Electrically controlled release of insulin using polypyrrole nanoparticles. Nanoscale 9(1), 143–149 (2017). (Polypyrrole conductive polymer nanoparticles for triggered release).

- Stimuli-Responsive DNA Nanostructures for Drug Delivery and Biosensing. RSC Chem. Biol. (2025). (DNA hydrogel networks formed by complementary strands and RCA with stimuli-responsive behavior).

- Aptamer-functionalized hydrogels for biosensing and controlled release (Ji et al.; Hao et al., adapted). Aptamer-functionalized hydrogels: An emerging class of biomaterials (2019 review detailing hydrogels with aptamer crosslinks for molecular responsiveness).

- Aptamer-Functionalized Natural Protein-Based Polymers as Innovative Biomaterials. (Review showing hybrid polymer-aptamer biomaterials in therapeutic contexts).